Hepatitis B Virus (HBV)

Jennifer Maclachlan, Benjamin Cowie, David Isaacs, Joshua S Davis

Recommendations

- Offer testing for hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection to all.

- A complete HBV blood test includes HB surface antigen (HBsAg), HB surface antibody (HBsAb), and HB core antibody (HBcAb).

- If HBsAg is positive, further assessment and follow up with clinical assessment, abdominal ultrasound and blood tests is required (see text).

- Household and sexual partners of people who are HBsAg positive should be offered testing, and vaccination if they are susceptible to HBV.

- If HBsAg positive, test for and vaccinate against hepatitis A

Overview

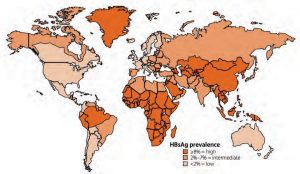

Approximately 1% of the Australian population – 220,000 people – are living with chronic HBV; however, it is estimated nearly half remain undiagnosed. People born overseas represent the majority of individuals with hepatitis B in Australia. Approximately 90% of the world’s population live in areas where the prevalence of chronic HBV in the population is 2% or higher, including the majority of source countries for Australia’s humanitarian intake.

A number of studies have assessed the prevalence of chronic HBV in refugees based on routine screening. Rates vary, but are significantly higher than the prevalence in the Australian population. Examples include predominantly Sub-Saharan African refugee cohorts in Melbourne (22%107 and 8%108) and Sydney (4%45), and from the Migrant Health Unit in WA (5%41). High prevalence has also been found among Burmese refugees (14%48 and 10%43), and those from the Mekong region (8–9%109). See prevalence tables for more information.

Since chronic HBV is a) generally asymptomatic; b) endemic in nearly all current countries of origin of people from refugee-like backgrounds, and c) has effective treatment and vaccination available, we have recommended universal testing.

Figure 4.1: Global Prevalence of Hepatitis B, 2012

Source: B Positive: All you wanted to know about hepatitis B110

* For multiple countries, estimates of prevalence of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), a marker of chronic HBV infection, are based on limited data and might not reflect current prevalence in countries that have implemented childhood hepatitis B vaccination. In addition, HBsAg prevalence might vary within countries by subpopulation and locality. Adapted from: World Health Organisation, Introduction of hepatitis B vaccination into child immunization services. WHO. 2001.

Chronic HBV is usually asymptomatic; however, if left undiagnosed and unmanaged it can cause advanced liver disease and/or liver cancer in up to 1 in 4 people. Appropriate management and treatment significantly reduces these risks; and diagnosis also provides an opportunity to offer vaccination to contacts at risk of exposure.

Investigations

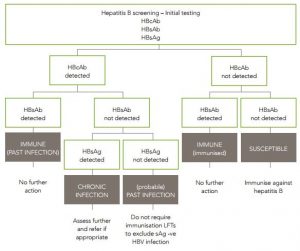

Serology testing for HBV infection should include hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), hepatitis B surface antibody (HBsAb or anti-HBs) and hepatitis B core antibody (HBcAb or anti-HBc). All three tests are rebatable by Medicare if the request specifies ‘query chronic HBV’ (or similar). Testing all three markers allows a complete picture of hepatitis B status, including clarification of infection, and immunity, and whether immunity has developed in response to vaccination or infection. All tests should be performed with the informed consent of the individual, or their legal guardian where relevant (e.g. parents providing consent for children).

Figure 4.2: Serology interpretation for hepatitis B

Source: Decision Making in Hepatitis B (ASHM resource)

| HBsAg | positive | Chronic HBV infection |

| anti-HBc | positive | |

| anti-HBs | negative | |

| HBsAg | positive | Acute HBV infection *(high titre) |

| anti-HBc | positive | |

| IgM anti-HBc* | positive | |

| anti-HBs | negative | |

| HBsAg | negative | Susceptible to infection ( vaccination should be recommended) |

| anti-HBc | negative | |

| anti-HBs | negative | |

| HBsAg | negative | Immune due to resolved infection |

| anti-HBc | positive | |

| anti-HBs | positive | |

| HBsAg | negative | Immune due to hepatitis B vaccination |

| anti-HBc | negative | |

| anti-HBs | positive | |

| HBsAg | negative | Various possibilities including: distant resolved infection, recovering from acute HBV, false positive, ‘occult’ HBV |

| anti-HBc | positive | |

| anti-HBs | negative |

Management and Referral

Further testing and management is required for all people diagnosed with chronic HBV, alongside culturally appropriate counselling about their diagnosis, treatment options, and ways to minimise the impact of HBV on their health and reduce transmission to others. There is no such thing as a ‘healthy carrier’. All people with chronic HBV infection need lifelong monitoring, as HBV infection is a dynamic process. Consultation with a clinician experienced in the management of viral hepatitis is recommended. Consider the patient’s language proficiency and the use of an interpreter when discussing HBV diagnosis, management and treatment. Use visual material if the patient has low literacy skills (see resources below).

All those who are HBsAg positive should have:

- Counselling regarding the natural history, how to protect others from infection, the need for lifelong monitoring and the avoidance of hazardous alcohol consumption.

- A targeted history and physical examination, looking for symptoms or signs of chronic liver disease.

- Baseline LFTs, HBV viral load, HB eAg and eAb, FBE, iron studies, INR, UEC and upper abdominal ultrasound.

- Serology for hepatitis A virus (HAV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), hepatitis delta virus (HDV) and HIV if not already completed.

- A repeat consultation once these results are available, to decide on a management plan, and whether specialist referral is needed.

- The following patients should be referred to a specialist (ID physician, gastroenterologist or GP with accreditation to prescribe HBV medications):

- anyone suspected to have cirrhosis (based on clinical signs of chronic liver disease, imaging findings, low platelets or albumin, high bilirubin or INR)

- raised ALT (>19IU/L for women or >35IU/L for men, > reference range for children) AND HBV viral load >2,000 IU/ml

- current pregnancy

- those with co-infection with HIV, HCV or HDV (in addition to HBV)

- those with extra-hepatic manifestations of HBV (such as vasculitis or glomerulonephritis).

- All others with HBV should have a management plan made, which should include a clinical review and a blood test for LFTs every 6 months and HBV viral load every 12 months.

- The following patients with chronic HBV infection should be offered surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), with 6 monthly ultrasound and serum Alpha Fetoprotein (AFP):

- African people over age 20 years

- Asian females over age 50 years

- Asian males over age 40 years

- anyone with proven or suspected cirrhosis

- anyone with a family history of HCC in a first or second-degree relative.

- People with HBV who are non-immune to hepatitis A should be vaccinated against HAV.

For people from refugee-like backgrounds who remain susceptible to HBV infection (i.e. negative serology for HBsAg, HBsAb and HBcAb), vaccination against hepatitis B is recommended at all ages.

Household and sexual partners of people with hepatitis B infection should be tested for HBV and vaccinated if they are susceptible to HBV infection. Serological testing (to confirm HBV immunity) is recommended for sexual partners and household or other close household-like contacts of people who are infected with hepatitis B, 4–8 weeks after completion of the primary vaccination course.

Figure 4.3: Testing algorithm for hepatitis B

Considerations in Pregnancy and Breastfeeding

All pregnant women should be screened for hepatitis B, and if they are HBsAg positive, they should be appropriately assessed, including hepatitis B viral load testing, ideally at 18–24 weeks of pregnancy. It is important that women who are diagnosed with hepatitis B antenatally are referred to a viral hepatitis specialist during pregnancy and that they engage in ongoing monitoring and care following delivery.

If a woman is HBsAg positive, her infant should receive hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIG) in addition to standard birth dose of monovalent hepatitis B vaccination, to reduce the risk of HBV transmission. HBIG and hepatitis B vaccination can be given concurrently to the infant (administered in different sites). HBIG should preferably be given within 12 hours of birth, and should be given within 48 hours. Hepatitis B vaccination should preferably be given within 24 hours and should be given within 7 days. Infants should go on to complete routine hepatitis B vaccination. Antiviral treatment to further reduce risk of vertical transmission is increasingly used in pregnant women with a high viral load (>107 IU/ml). Caesarean section is not recommended as an intervention to reduce the risk of perinatal hepatitis B transmission.

Breastfeeding is safe in women with chronic HBV, and does not increase the risk of transmission to the infant.

Considerations for Children

All children born in Australia should receive a full course of hepatitis B immunisation, which includes a dose within 24 hours of birth, and subsequent vaccinations at 2, 4 and 6 months (i.e. four doses of hepatitis B vaccine within the first year of life).

Children born to mothers with chronic HBV should have hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIG) at the time of birth in addition to the routine hepatitis B immunisation schedule as above. All children whose mothers have chronic HBV should subsequently be tested for HBsAg and HBsAb to determine if they have been infected, at 3–12 months after their vaccination is complete (i.e. after 9 months of age). Serology should not be checked before 9 months of age (to avoid detection of HBsAb from HBIG given at birth.

Children with chronic HBV typically have minimal liver damage and rarely require treatment; however, this is not always the case. All children with chronic HBV should therefore be referred to a paediatric viral hepatitis specialist for ongoing assessment and management. Children typically have very high viral load. Basic advice about preventing transmission related to normal childhood activities (e.g. cleaning blood spills, covering scrapes and scratches, not sharing toothbrushes) and immunising household contacts (and checking seroimmunity) is essential.