Immunisation

Georgia Paxton, Gillian Singleton

Recommendations

- Provide catch-up immunisation so people from refugee-like backgrounds are immunised equivalent to an Australian-born person of the same age.

- Written records are considered reliable evidence of vaccination status.

- In the absence of written immunisation documentation, full catch-up immunisation is recommended.

- Routine serology against a range of vaccine preventable diseases (VPD) is not recommended to guide catch-up immunisation. Serology for hepatitis B infection and immunity is part of initial health screening. Offer testing for:

- varicella serology (if ≥14 years if there is no history of natural infection)

- rubella serology (in women of childbearing age).

- Do not presume other providers are completing immunisation catch-up – be opportunistic – immunisation is the responsibility of all health providers.

Overview

People from refugee-like backgrounds are at significant risk of being unimmunised or under- immunised on arrival in Australia, due to their refugee and forced migration experience. Source country immunisation schedules225 are different to the Australian immunisation schedule,101 meaning no one will arrive fully vaccinated. Humanitarian crises are associated with disruption of health services and immunisation programmes, leading to issues with vaccine access and quality.226 Humanitarian entrants to Australia may receive polio vaccine prior to departure, and/or limited vaccines as part of the voluntary Departure Health Check (DHC);a,20 however, other humanitarian entrants may not be immunised and Expanded Programme of Immunisation (EPI) records are not required prior to travel. Asylum seekers will not be immunised prior to travel. Refugee and asylum seeker communities are also identified as being ‘at-risk’ of vaccine preventable diseases (VPD) after arrival,226 and there have been reported outbreaks of VPD related to refugee index cases.227–229

Although refugees may have received immunisations overseas, most do not have documentation of immunisation. There is often a clear verbal history of vaccinations, although there is debate on the validity of parental/self-recall of vaccination status.230–235 Written records are considered reliable evidence of vaccination status if available. In the absence of written immunisation documentation, full catch-up immunisation is recommended.236

There are limited recent Australian prevalence data on refugee immunisation – available studies show:

- 44–53% of asylum seekers still require catch-up immunisation on release from detention.237,238

- 50–98% of adult refugees from African and Asian source countries have incomplete immunisation according to the Australian schedule.

- 90–98% of child refugees (mixed cohorts) have incomplete immunisation according to the Australian schedule.39,108,231,239

Available data suggest the following prevalence of serological immunity (reviewed in239):

- Adults: Measles 87–95%, Mumps 84–96%, Rubella 62–96%, Tetanus 33–47%, Diphtheria 66%, Hepatitis B 49–60%.

- Children: Measles 56–90%, Mumps 60–93%, Rubella 74–85%, Tetanus 52–88%, Diphtheria 45–69%, Hepatitis B 26–66%.

Limited data suggest that immunity to all components of combination vaccines (e.g. serological immunity to all three of measles-mumps-rubella) is much lower.43,46,231,240

Every attempt should be made to provide catch-up immunisation so people from refugee-like backgrounds are immunised equivalent to Australian-born people of the same age.

History and Examination

Assess any existing written immunisation records – overseas records (may require translation), detention health summaries for asylum seekers, other immunisation records, including the Australian Childhood Immunisation Register (ACIR) for children where vaccines were given aged <7 years. The expansion of ACIR to include all children and young people <20 years of age from 2016 will allow improved recording and review of previous immunisations.

Consider vaccines given as part of the DHC for offshore refugee arrivals – Mumps-Measles-Rubella (MMR) in people aged 9 months – 54 years, Yellow Fever (YF) and also Oral Polio Vaccine (OPV) depending on port of departure – these are all Live Viral Vaccines (LVV).19 Live attenuated vaccines (LAV), including LVV, should be given simultaneously, or at least 4 weeks apart. DHC immunisation may affect the timing of immunisation catch-up and also the interpretation of tuberculin skin tests (TST).

Assess for a clinical history of varicella infection.

Clarify hepatitis B status (for the individual and their household contacts) from initial post-arrival screening. This test may have been performed as part of pre-departure screening in unaccompanied or separated minors and pregnant women.

Consider the timing of the TST in relation to LAV administration – where TST is used for tuberculosis (TB) screening (i.e. in children). TST should be administered either before, or 4 weeks after LAV.236

Clarify whether immunisation has been commenced since arrival and if there is a catch-up plan in place. Asylum seekers who have been in held detention may have received some immunisations and they will have a written record.

Assess for any contraindications to immunisation or particular vaccines, completing the pre-vaccination screening checklist and relevant responses (tables 2.1.1. and 2.1.2 in the Australian Immunisation Handbook).236

- Absolute contraindications include anaphylaxis following a previous dose/any component of the relevant vaccine.

- LAV should not be administered to significantly immunocompromised people. MMR, varicella and zoster vaccines can be administered to people with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infection who are mildly immunocompromised, after specialist advice.

- Consider pregnancy in all females of childbearing age, including in adolescents. In general, LAV should not be administered during pregnancy, and women should be advised not to become pregnant within 28 days of receiving a LAV.236

Assess for the presence of a Bacillus Calmette Guerin (BCG) scar (deltoid, forearm, scapula, both sides and may be elsewhere). BCG vaccination leaves a scar in 92%–100% of recipients in prospective studies.241–243

Consider any medical conditions requiring extra vaccine protection including anatomical or functional asplenia, HIV infection or other forms of immunosuppression, severe or chronic medical conditions or hepatitis B (where hepatitis A vaccination is recommended in the absence of immunity).236 Consider any occupational risk factors requiring extra vaccine protection (e.g. healthcare workers (hepatitis B vaccine, influenza vaccine) or occupational animal exposure/abattoir workers (Q fever)).

a In 2016 extended screening will be implemented for the Syrian cohorts, with additional immunisations (MMR, polio vaccination and diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccination – in the form of hexavalent or pentavalent vaccine in children <10 years – check available paperwork)

Investigations

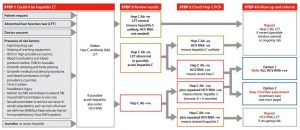

- Hepatitis B serology (see Hepatitis B) is part of initial post arrival health assessment. Hepatitis B serology is also recommended as part of routine antenatal screening for pregnant women in Australia. Adequate hepatitis B immunity is considered to be hepatitis B surface antibody (HBsAb) ≥10mIU/mL

- Rubella serology in women of childbearing age – rubella antibody (Ab) is recommended prior to each conception, or early in the pregnancy – rubella Ab titres can fall post vaccination, and previous protective titres are not considered reliable evidence of immunity. Adequate rubella immunity is considered to be an Ab level above the accepted cut-off point for a given commercial assay (the WHO cut-off for adequate immunity is >10IU/mL). Women should be advised of their test result, as it is a clinically significant test.244

- Varicella serology in people aged 14 years and older without a natural history of varicella infection.236,245,246

Routine serology against a range of VPD is not recommended to guide catch-up immunisation.236 Serology is not available for all vaccines, serological testing may not be reliable for vaccine-induced immunity, and immunity against a particular VPD may not change the vaccines required (with the use of combination vaccines). Serological testing prior to vaccination is cost effective for varicella245–247 hepatitis B248 and hepatitis A.249,250

Post-vaccination serology for hepatitis B is recommended for:

- infants born to mothers with hepatitis B

- people at significant occupational risk

- people at risk of severe or complicated hepatitis B disease

- household/sexual/close contacts of people with hepatitis B.

Check HBsAb 4–8 weeks after completing the primary vaccine course (3–12 months after completing the primary vaccine course in infants). If HBsAb <10mIU/mL – exclude Hepatitis B infection (HBsAg and HBcAb) then repeat single booster dose. If HBsAb remains <10mIU/mL 4 weeks after the booster dose, provide 2 further booster doses one month apart. If HBsAb remains <10mIU/mL refer to specialised immunisation service for consideration of intradermal hepatitis B vaccine.

Management

There is high quality evidence and a strong recommendation for immunisation236 and moderate250 to high251 quality evidence and a strong recommendation for catch-up immunisation in refugees.

Develop a catch-up immunisation plan – see table 12.1 and 12.2.

- Determine which vaccines have already been given – written records are considered reliable evidence of previous vaccination.

- Aim for minimum number of visits, and minimum dosing schedules – therefore include vaccines where more doses are required (generally DTP, IPV, Hepatitis B, HPV) in the initial visit (see table 12.2). In general, catch-up immunisation can be provided over 3 visits, across 4 months in adolescents and adults (i.e. by giving the 3rd doses of DT containing and hepatitis B vaccine at the same visit), although recent changes to pertussis dosing and combination meningococcal vaccination may extend this to four visits for children <10 years. Where possible, immunise family members simultaneously to reduce the total number of immunisation visits.

- Give combination vaccines where possible (to reduce the number of needles).

- Consider formulations/licensing and age restrictions.

- Consider recent or pending schedule changes.

- Complete, but do not restart, immunisation schedules if there is written documentation of previous vaccine doses.

- Provide opportunistic immunisation where possible, but do not interrupt other providers’ immunisation delivery if catch-up plans are in place.

Provide a written record and a clear plan for ongoing immunisation. It is useful to document which dose is being given e.g. MMR dose 1 of 2.

Vaccination information should be entered into the Australian Childhood Immunisation Register for children and young people <20 years (ACIR is transitioning to become the Australian Immunisation Register – AIR). From late 2016 it will be possible to enter data across the lifespan. This is intended to support changes to immunisation requirements for Centrelink payments, including those for childcare, after-school care, and Family Tax Benefit supplements. Children will need up-to-date immunisation records, or will need to have a catch-up plan in place, in order for families to access these payments, and refugee-like families may be particularly vulnerable to changes in Centrelink support.

For most vaccines, there are no adverse events associated with additional doses in already immune individuals. Frequent additional doses of DT-containing vaccines and pneumococcal polysaccharide (PS) vaccines (PS vaccines are not part of the catch-up schedule) may be associated with increased local reactions. If large local reactions occur with DT-containing vaccines, review prior to giving further doses, although the benefi of protection may outweigh the risk of an adverse reaction (e.g. protection against pertussis from a booster dose of diphtheria-tetanus-acellular pertussis).236

For families outside the initial stage of settlement – remind them to plan early for travel immunisations in the future. See www.cdc.gov/travel for information on destinations and vaccine requirements.

Considerations in Pregnancy and Breastfeeding

LAV (MMR, MMR-Varicella (MMR-V), Varicella Virus (VV), Zoster, YF, BCG, Rotavirus and oral Typhoid) are contraindicated during pregnancy and should not be given for 28 days prior to pregnancy.236

Considerations in Children

Consider the impact of age and how the child’s age relates to the Australian immunisation schedule delivery points (e.g. 9-year-old child who will turn 10 years before completing catch-up – thus changing vaccine formulations; consider which vaccines will be given in the future when the child reaches the schedule age).

Use positioning, distraction and measures to reduce vaccine-associated pain.236

Children aged <12 months are immunised in the anterolateral thigh or ventrogluteal area, after the age of 1 year vaccines can be given in the deltoid area of the upper arm.101 Usually only 2 injections per limb is practical.

Infants born to mothers with hepatitis B must have a birth dose of hepatitis B vaccine (preferably within 24 hours and definitely within 7 days) and also hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIG) – given in separate thighs – see Immunisation Handbook.

Links

Australian Immunisation Handbook

WHO monitoring – vaccination schedules by country

Royal Children’s hospital – catch up immunisations in refugees

Melbourne Vaccine Education Centre (MVEC)

National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance (NCIRS) – Fact Sheets

Foreign vaccine products/naming (CDC)

Translated immunisation resources